The best way to align ourselves with our readers' needs is to get direct feedback from them. But we also need to ensure that the feedback we get is clear and focused, and not vague and hard to implement. To collect feedback, but be unable to act upon it because it is not clear to us what the problem is and what we need to do about it, is perhaps worse than not collecting any feedback at all.

To improve our documentation quality (DQ), the feedback we collect must be both meaningful and actionable:

- Meaningful feedback requires readers to focus only on the important issues.

- Actionable feedback requires us to be able to take what our readers tell us and do something about it.

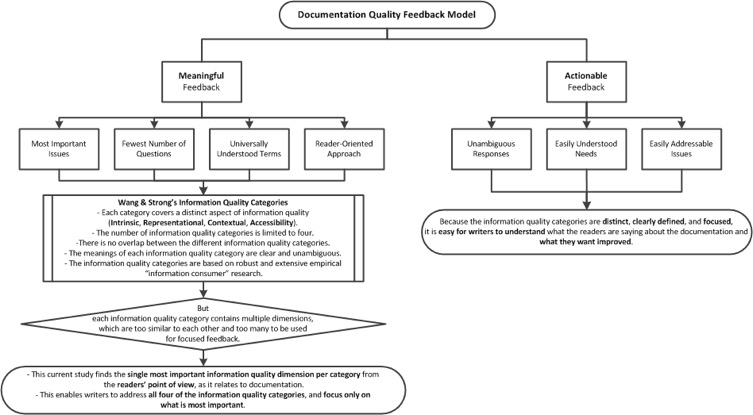

This article proposes a preliminary, focused, clearly defined, and reader-oriented model for collecting meaningful and actionable DQ feedback, based on well-known, empirically tested information quality categories and dimensions.

Defining documentation quality

Before we can collect meaningful and actionable feedback from our readers about the quality of our documentation, we first need to understand what DQ means to readers.

To properly define DQ, we must meet the following criteria:

- The definition must be from the reader’s point of view: Because readers alone determine if the document we give them is high-quality or not, any definition of DQ must come from the readers’ perspective. We can come up with any number of quality attributes that we think are important, but at the end of the day, what we think is not as important as what our readers think.

- The definition must be clear and unequivocal: Both readers and writers have to "be on the same page" when it comes to what makes a document high-quality. Misunderstandings of what readers actually want from documentation are a recipe for unhappy readers.

- The definition must cover all possible aspects of "quality": Quality is a multidimensional concept, with both objective ("meets requirements") and subjective ("meets expectations") dimensions, and we must be sure that any attempt to define it is as comprehensive as possible. A definition that emphasizes one dimension over another, or leaves one out altogether, cannot be considered a usable definition.

- The definition must have solid empirical backing: To be considered a valid definition of DQ, serious research must be done to give it the proper theoretical underpinnings. Years of experience or anecdotal evidence can act as a starting point, but if we are serious about our professionalism and our documentation, we need more.

Building a comprehensive definition of DQ

To meet all of these criteria, I turned to a fascinating study done in 1996 by Dr. Richard Wang (co-director of the MIT Total Data Quality Management Program) and Dr. Diane Strong (director of the Management Information Systems Program at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute).

They developed a comprehensive, hierarchical framework of information quality attributes that were important to information consumers. Their underlying assumption was that to improve information quality, they needed to understand what it meant to information consumers – information quality cannot be approached intuitively or theoretically because these do not truly capture the voice of the information consumer.

Their framework was made up of 15 quality dimensions, grouped into four quality categories – Intrinsic, Representational, Contextual, and Accessibility. Subsequent research on this framework has found that it works very well in identifying and solving information quality issues, and that its underlying methodology (information categories and dimensions) are robust and applicable to real-life situations.

Applying Wang & Strong's information quality categories and dimensions to document quality, we get the following definitions:

- Intrinsic DQ (IDQ): The information in the documentation must have quality in its own right. This category is made up of the following dimensions:

- Accurate: The information in the documentation is correct, reliable, and certified free of error.

- Believable: The information in the documentation is true, real, and credible.

- Objective: The information in the documentation is unbiased (unprejudiced) and impartial.

- Reputable: The information in the documentation is trusted or highly regarded in terms of its source or content.

- Representational DQ (RDQ): The information in the documentation must be well represented. This category is made up of the following dimensions:

- Concise: The information in the documentation is compactly represented without being overwhelming (that is, it is brief in presentation, yet complete and to the point).

- Consistent: The information in the documentation is always presented in the same format and is compatible with previous data.

- Easy to understand: The information in the documentation is clear, without ambiguity, and easily comprehended.

- Interpretable: The information in the documentation is in an appropriate language and units, and the definitions are clear.

- Contextual DQ (CDQ): The information in the documentation must be considered within the context of the task at hand. This category is made up of the following dimensions:

- The appropriate amount: The quantity or volume of the available information in the documentation is appropriate.

- Complete: The information in the documentation is of sufficient breadth, depth, and scope for the task at hand.

- Relevant: The information in the documentation is applicable and helpful for the task at hand.

- Timely: The age of the information in the documentation is appropriate for the task at hand.

- Valuable: The information in the documentation is beneficial and provides advantages from its use.

- Accessibility DQ (ADQ): The information in the documentation must be easy to retrieve. This category is made up of the following dimensions:

- Accessible: The information in the documentation is available or easily and quickly retrievable.

- Secure: Access to the information in the documentation can be restricted, and hence, kept secure.

Based on Wang and Strong's IQ framework, I set out to create a model for collecting meaningful and actionable feedback from readers, based on how they define DQ. To be credible, this model must:

- Focus only on the most important issues

- Contain the fewest possible number of questions

- Use universally understood terminology

- Approach the issues from the readers' point of view

- Collect unambiguous responses from readers

- Enable writers to easily understand and address readers' issues

Wang and Strong's IQ framework enables us to meet all of these criteria:

- There are only four IQ categories:

- Intrinsic

- Contextual

- Representational

- Accessibility

- Each category covers a distinct measurement of information quality with no overlap between them.

- The categories are based on robust and extensive user research, and their meanings and dimensions are succinct and clearly understood.

Unfortunately, there are a few drawbacks with directly using Wang and Strong's information quality framework for collecting DQ feedback:

- The categories do not lend themselves easily to the creation of feedback questions – for example, we cannot ask readers, "How was the intrinsic quality of the documentation?"

- The gradations between each category’s dimensions are too fine to be used for focused feedback.

- There are too many dimensions for practical use.

Given these issues, I focused on limiting the number of information quality dimensions I could use to define DQ. My approach was to find the single most important information quality dimension for each of the four categories (as readers rated them), which would then be used to represent the entire category. These four DQ dimensions (one per category) would then serve as the basis for a DQ feedback model. A schematic diagram of the proposed DQ feedback model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: DQ feedback model

Methods

A questionnaire was developed asking readers to rate Wang and Strong's information quality dimensions by their perceived importance on a nine-point Likert-type scale, (1 = "extremely important" to 9 = "not important at all"). The questionnaire was sent to customer service personnel in various companies, who were asked to send it on to their readers. This was done to ensure that a broad, worldwide range of readers from different fields answered the questionnaires, and that the people answering the questions were the people who actually read and used the documentation.

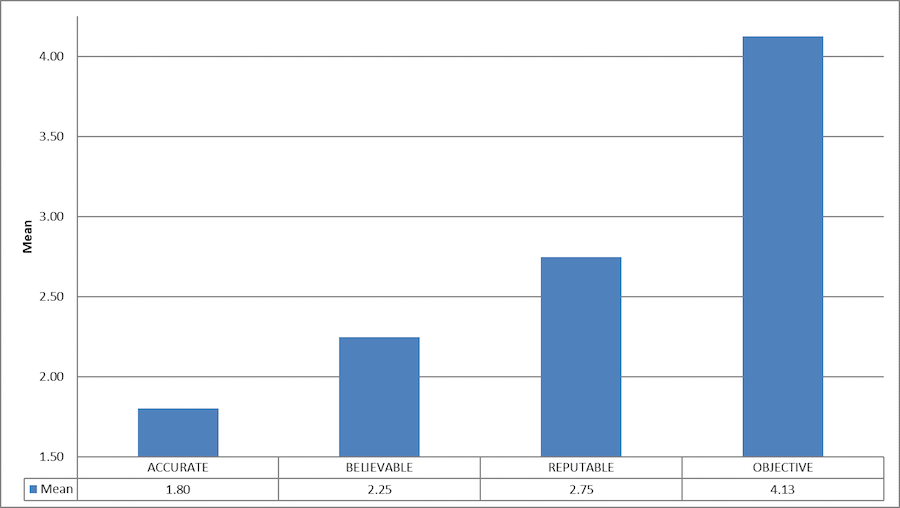

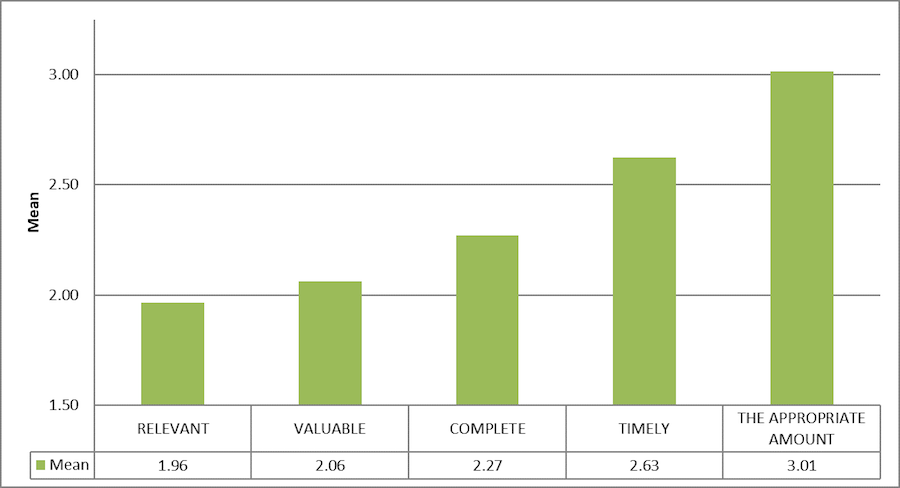

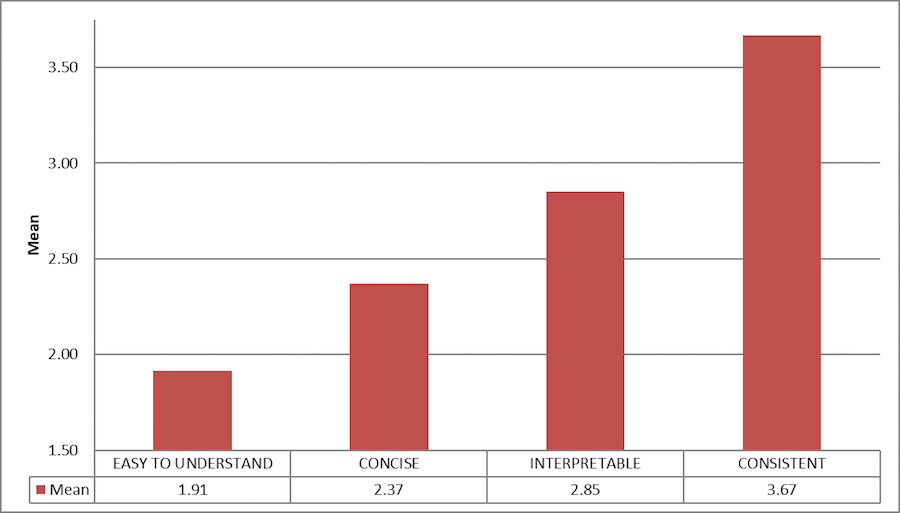

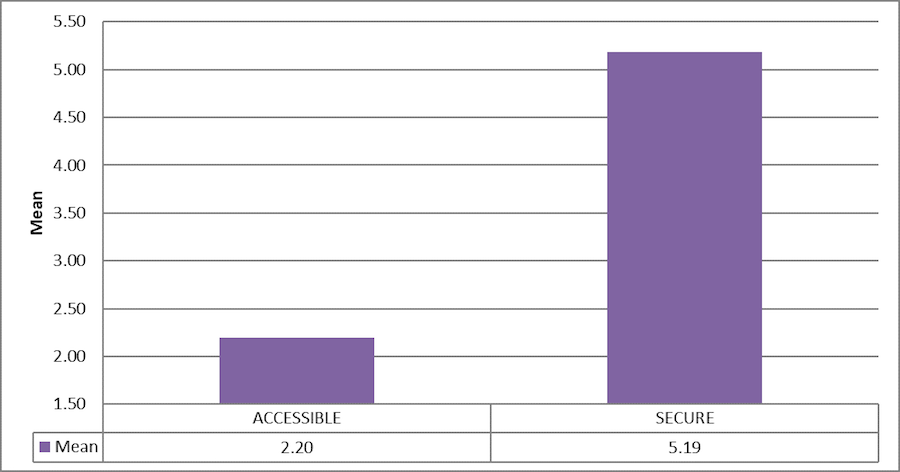

The dimensions were sorted by information quality category, and the mean weight of each of them was calculated – the lower the weight, the more important the dimension. For each information quality category, the dimension with the lowest rating was considered to be the most important and represented the entire category.

Results

A total of 81 readers responded to the questionnaire, but only 80 of them rated all of the IQ dimensions. The following figures show the ratings for each of the DQ categories (these are weighted averages; the lower the number, the more important the dimension):

Figure 2: IDQ ratings

Figure 2: IDQ ratings

Figure 3: CDQ ratings

Figure 4: RDQ ratings

Figure 4: RDQ ratings

Figure 5: ADQ ratings

Figure 5: ADQ ratings

Analysis

The goal of this study was to create a model for collecting meaningful and actionable DQ feedback based on Wang and Strong's information quality categories and dimensions, using readers' definitions of DQ.

The results of the readers' ratings show that readers expect the documentation they get to be accurate, relevant, easy to understand, and accessible (AREA). Although this might seem self-evident, it provides a strong empirical underpinning for the claim that DQ can be defined using a small yet comprehensive set of clear and unambiguous IQ dimensions.

Practical applications of the DQ feedback model

This study takes Wang and Strong's information quality categories and dimensions and applies them to DQ. By asking readers to rate the different dimensions that make up each category, I was able to find the single most important IQ dimension per category and create a reader-oriented DQ definition:

- Intrinsic = Accurate

- Contextual = Relevant

- Representational = Easy to Understand

- Accessibility = Accessible

Because these IQ categories are distinct, clearly defined, and focused, we can use the representative DQ dimensions to easily understand what our readers are telling us about the documentation (meaningful feedback) and what they want improved (actionable feedback).

The proposed DQ feedback model asks readers only the following questions:

- Could you find the information you needed in the document?

- Was the information in the document accurate?

- Was the information in the document relevant?

- Was the information in the document easy to understand?

These four questions cover all aspects of DQ and can be applied to all methods of collecting feedback. For example, technical communicators can sit in on customer product training sessions and ask the participants to note any problems they come across in the documentation. Working together with trainers, technical communicators can collect a great deal of meaningful and actionable feedback from real users by asking them to focus only on the four AREA DQ dimensions when they work with the documentation.

Providing reliable methods and metrics for measuring DQ

The AREA DQ dimensions that make up the reader-oriented definition of DQ at the heart of this proposed feedback model can also be used to classify and sort existing internal or external feedback. This can then be presented to management as clear and reliable metrics about the documentation that will help determine where more emphasis might need to be invested.

For example, if the feedback received indicates that a majority of the issues are about the accuracy and relevance of the documentation, then management can make a clear decision about who in the organization is responsible for addressing these issues and can later compare before-and-after feedback to see if the percentage of these complaints has decreased.

Similarly, technical communicators (who, by and large, are responsible mainly for the easy-to-understand dimension) can show their managers how good writing can lower complaints about this issue.

Conclusion

This article presents only a preliminary study intended to create a framework for a DQ feedback model based on empirically tested and distinct information quality categories and dimensions, and using a reader-oriented definition of DQ. Deeper statistical analyses were done on the results to validate their reliability and robustness; this is outside the scope of this article (for the full study and further applications of the model, see Strimling [2]). Nevertheless, it is clear that this empirically based model can enable technical communicators to collect meaningful and actionable DQ feedback; anecdotally, technical communicators who have used this model in the field have reported successes; I hope that you will achieve this as well.

Further reading

Strimling, Y. (2019). "Beyond Accuracy: What Documentation Quality Means to Readers."Technical Communication, 66(1), 7-29